Paola De Pietri (Reggio Emilia, 1960) and Lala Meredith-Vula (Sarajevo, 1966) have in common their use of the same instrument: the camera. To a certain extent, they also make a similar use of it as an instrument to analyse certain forms of life (Wittgenstein) and almost always conflictual relationships between different levels of reality, habits, lifestyles, and contexts. They both observe the world in order to reveal the complexity and disarticulation of dimensions and experiences that characterise our global age.

And yet both Paola De Pietri and Lala Meredith-Vula go beyond this initial conceptual level of the project and method, and also beyond the formal level of documentary photographic technique. They do so in order to create forms of rare beauty in which poetry prevails over information, symbolic function over communication, the ineffable cognitive experience of art over theoretical awareness, and an ecmnesic (Barthes) and expressive (Deleuze) vision over that of illusion and reproduction. We may see photographs, but between the instrument and the subject there is more the space of painting than that of cinema or television. In other words, both of them analyse, search, and investigate, but in point of fact they contemplate a reality from which they extract images that can be judged and enjoyed in terms of beauty alone. And this beauty is not simply an end in itself - it is not self-sufficient in formal terms. There is a coming and going and an exchange between the beauty of the image and the content itself. Within these striking images one can perceive stories and motives that are quite extraordinary. To paraphrase Pasolini, we might say that in this case things appear to be transformed into something perfect and special, and that beauty is as much a part of the drama and the event as the meanings that, in their various ways, both the author and the observer confer upon the images and the reality they portray.

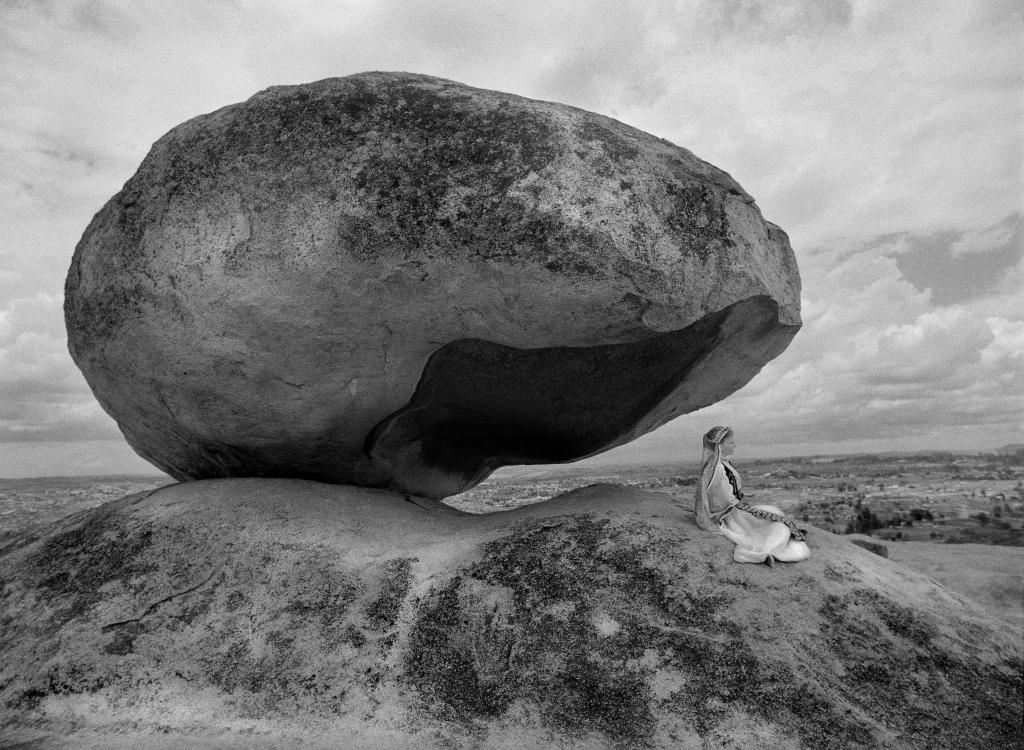

Through images of rare beauty and drama, Lala Meredith-Vula tells the tale of her land, and of the rift between a traditional world, with all its memory and traditions, and that of the modern day. The Sarajevo-born artist appears to go back to consider her cultural origins - what has been removed and all that is most familiar to her people: customs, landscapes, surroundings and rituals. Among her photographs we find a body immersed in a pool of water, in which some women can be seen washing themselves, as though for purification more than cleansing. There are ruins and children, and a series of photographs inspired by a kind of performance. Dressed in traditional Kosovar costume, the artist moves through a modern city, the countryside, and archaic places that appear to be lost in a time that is more mythical than historical. In one of these pictures, for example, we see the artist dressed as of old, sitting under an enormous boulder that looks like a meteorite or a chunk of mountain hurled down by a Titan. What is so striking is the disproportion between the rock and the little figure. It is this disproportion that makes the scene so violently dramatic, even though everything appears suspended in a legendary atmosphere. Time appears to stand still, as does the scene, the outcome of which we shall never know.

Also Paola De Pietri portrays the simple reality of our world, leaving it suspended in time. A time that restores a precious aura to the things of the world. In these unassuming and all too familiar situations we see women and children at the centre of a crossroads or on the kerbs in the suburbs, groups of foreigners feasting, remnants of countryside that still survive on the fringes of the metropolises and industrial areas, boys and girls lying down by lakes and rivers. The formal and symbolic breach between the art form and the reality which is analysed is that of the poetry and figurative beauty to which the two artists entrust both their message and their explicit and implicit declaration of intent.

In many ways, their compositions speak a figurative language which is that of painting: colour, lighting, framing, and perspective. But it is the language of great tradition. The scenes and genres we find in the art of Lala Meredith-Vula and Paola De Pietri refer back more to Renaissance painting than to the Romantics or moderns: en plein air landscapes in one case, and landscapes of the sublime in the other. Their special relationship with time and space is also a result of a shift in their poetic-figural horizon: from photography as a live account to photography as the transfigured image of a real experience - but one that is shattering or stunning, unexpected or shocking. We find an experience of the world and of its complex contemporary events that may also be phenomenological and anthropological. In other words, neither of them appears to be interested in explaining things, telling us how they occurred or why. For both of them, poetic narration has far greater meaning. It means telling the truth by using the language (insane-visionary-exclamatory-aureate) which blurs the borderlines between noumenal and phenomenal, and between reality and truth. But they do not simply apply some conscious theory. For this limitation or punctum can be achieved only by abandoning the safe vehicles of intellect and practicality, and accepting subordination to those of coincidence and possibly visionary inspiration, and of sensitive imagination. The reality of the image, which is thus iconic and that of sense, and is thus phenomenological, appears to be other than what we actually supposed, knew, or might have thought it to be. And beauty so often redeems and oversteps the conceptual and methodological structure itself. This explains why progress, for example, is so contradictory for these two artists. Anachronism is far more than a mere coming and going between different ages and periods of modern history. Indeed, life flourishes and people work and love, washing away their impurity amongst the ruins of civilisation. For civilisation is also this building up of ruins on which the Benjaminian angelus novus fleetingly dwells. Or again, tradition has its own precise, central role among our buildings and streets. This is a world of myth, of alienation and of the sublime. In other words, a place that is not that of the martyr or victim, nor of the marginalised and outcast. And so the angelus novus can recompose the broken through the body of the artist, who is the hero and incarnation of tradition and of all that exists and survives in this word. Revealing a future "progress" is not to be attained so much by the picturesque of anachronism as by the sublime of anachronism. And it is also true that landscape or maternity or the home or the family are not in themselves artistic subjects. They are genres and themes that appear to us with the power of Myth, as the result of an experience of reality that runs counter to the desacralising and demythicising power of progress.

Ian Jeffery writes: "The photographer makes judgements on what might be called a range of existential possibilities. She recognises a paradigm which takes into account the near and the far, with intervening stages. Here around us are the things that we can touch, and with which we are comfortable - and in whose presence she acts normally. Out there though exists society and the nation, in which context we don't altogether matter as individuals. In one poignant image she searches amongst the fragments and debris of a ruined building, looking for evidence. She is consulting history, which is not just a big idea but so complex as to be incomprehensible. History, represented by those shards, has reduced her, almost to the level of the fowls in the farmyard. But at one point she achieves equilibrium, standing in the rain in front of a memorial to a group of dead villagers, men and women. They had been killed by the roadside and the memorial, on a platform of rough concrete, does them honour one at a time. At some level they may represent history and the nation but the memorial remarks on them as individuals, fellow citizens and identifiable. Thus the relationship with the witness is symmetrical and homoeostatic: like greeting like. The memorial scene stands at the mid point in the paradigm, for, although it touches on both nation and history, the rain, the unfinished concrete and the commemorative pictures themselves refer us back to actualities, to the kind of environment in which we are most at home".

Paola De Pietri passes through the landscape in order to place the spectator in the spot traditionally occupied by the contemplator. A wood rustled by the wind, a flock of birds speckling the blue sky with myriad dots like frenzied ants or, on the contrary, the gentle sway of dunes, the musical variations of sea currents, or turmoil on the outer reaches of the galaxy. By doing so - and, I would say, by loving the external world as much as the rest of humanity - she restores things to time more than to space. These objects and events, which belong to us and to which we ourselves belong, are thus returned to the world of legend and to the sacrosanct, to wonder and disorientation. She winds her way through the theme of the other, of the foreigner and the hospes, so that we can think anew of the sacredness of home and family, which is seen here as a sheltering, familiar place, for both one and the other coincide in the lives of human beings. Paola De Pietri has long been photographing the new inhabitants of the suburbs. Her subject is suddenly no longer exodus and migration, but rather something at the heart of beauty and human dignity, wherever she may be, for she recreates family ties, establishing rites and ceremonies to give the highest and most archaic sense and value to her passage from one end of the planet to the other.

So when Paola De Pietri seeks otherness and diversity, she is essentially in pursuit of a different time. Photography is the means she uses to slow down the rhythm of this time, the flow of visions and the impressions of reality itself. This deceleration leads to unique experiences, opening up to the other and to the unforeseen. And the "other" is the dissimilar or the foreigner, the marginalised or the outcast. The unforeseen may be a landscape, a detail, an oblique view, or a situation. But it is nevertheless a revelatory manifestation of a different or unexpected time of existence. An existence immediately characterised by a special aura, as Walter Benjamin would say.

When we observe the world through this time (the duration of which is described both by Merleau-Ponty and Roland Barthes), it is as though things might still be caught up at a magical and astonishing distance. An insurmountable distance that turns them into icons. And, like icons, objects and people are portrayed by Paola De Pietri with a close eye on detail and veracity. And yet they are given shape by an indelible but significant metaphysical form of representation. They are figural forms rather than figurative reproductions, sought in the passing of everyday time and lifted out of the reality that would hold them hostage. Now at last they emerge from the stream of time to become authentic, absolute creatures. Or possibly they are authentic because they are unique and absolute.

The objects, landscapes and people we see are thus truer than life. And this is precisely where their authenticity and ontological basis begins. To nominate them means seeing and encountering them, not in our monitoring world but in a no man's land that is closer to the beyond than to the before, to the origin of all, to their essence without us.

More than within space, objects and people are resurrected in a time that is that of their original coming into the world. Like Lala Meredith-Vula, Paola De Pietri also starts out from art to encounter the world and, through beauty and truth, she once again provides an opportunity for conflictual or alienating cognizance. Immortalised like the bourgeoisie in a déjeuner sur l'herbe, her families of migrants demolish the myth of Western painting and offer the manifesto of a new beginning - that of resting on a flight. The works of both artists contain the same request - to stop the passing of time, and to return to places in the knowledge that something precedes us and sets us up as individuals, communities, and masses. They invite us to reconsider the critical aspects of our globalised age through the eyes of beauty and poetry.